First off, tell us about yourself:

My name is Joel Bray, I’m from Orange and I am Wiradjuri.

Tell us about the title ‘Dharawungara’ where does the name of your new work come from?

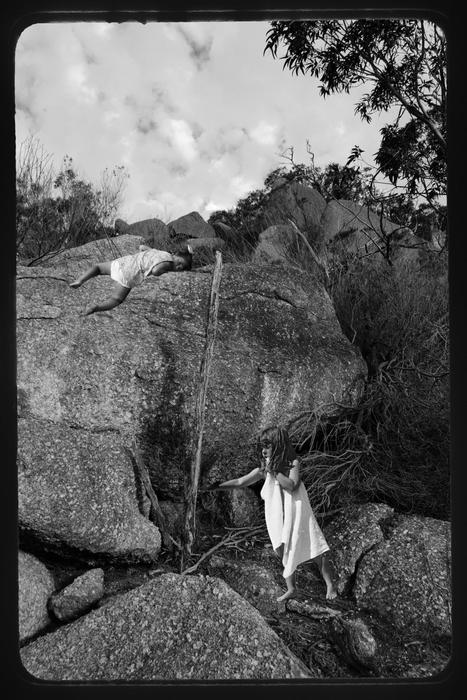

So for an exact translation of Dharanwungara, you have to break it up between ‘Dharawuny’ and ‘gara’. ‘Dharawuny’ means an archway or a passage and Dharawungara means to enter the passage or to pass through an archway. So it refers to a particular moment in ceremony where a ceremonial archway is created out of two saplings tied together and I was really intrigued by this because that kind of idea actually really occurs in rituals across the world or all throughout history. You know this idea when you get married you pass through people throwing confetti, or Jewish people get married under the chuppah. That kind of idea that represents the transition of going from one state to another. That’s basically what I’ve been exploring, rites of passage in a general sense about the way we all have created these rituals to collectively celebrate the transition from one state to another

Whether that’s unmarried to married or from a child to an adult or from follower to a leader.

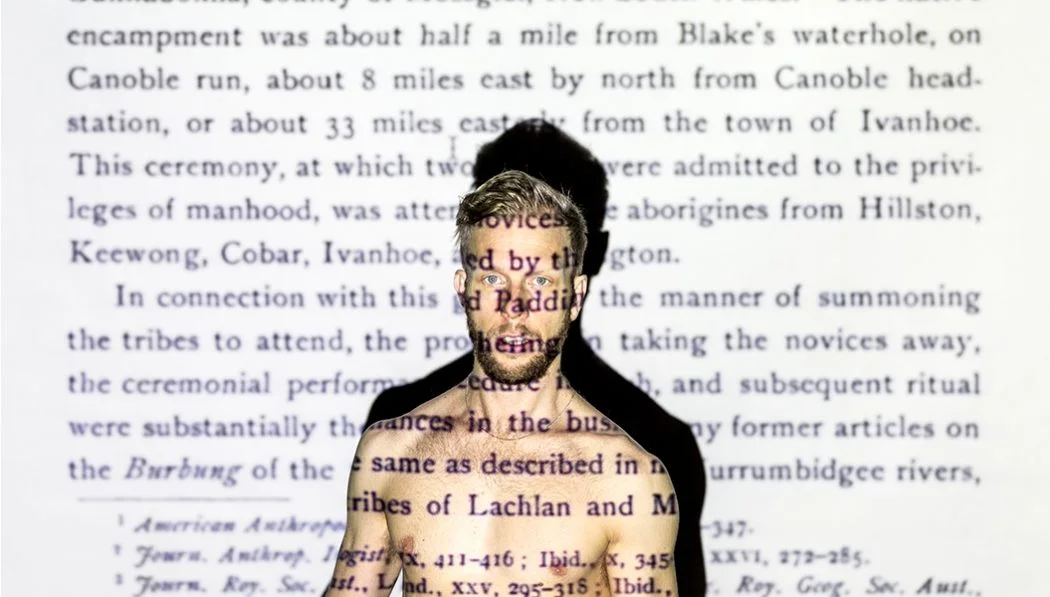

This new work has been described as creating an ‘intersection between ancestral ceremonial practice, collective imagination and the realities of colonization’ – what does this look like? Or how does this feel for an audience member?

I think in some ways the work is very much me. I’m performing solo and it’s me Joel Bray son of a Wiradjuri man searching for the rituals of his ancestors. So those three things are that, there’s ancient ritual practice that is still alive, it’s eternal even if it is not right now. Collective imagination is this idea that rituals by their nature are collective and communal they’re things that join us. We can reignite or breathe life back into an ancient ritual by jointly recreating it, and the realities of colonisation is that this ceremony and our language was literally beaten out of us. So it’s the collision of those three things, its an appeal from me to the audience to breathe life into this ancient ritual by being there in the space and to collectively imagine something old as new.

What have you enjoyed most about this development process?

It’s been a wrestle. It’s been hard. Because I’m actually in a bit of a dilemma, because how do you create a ritual that you don’t know? And it’s a solo and I’ve been on my own. But the best parts have been improvising, reading and writing and then immediately improvising in response to that. That has felt really special. I’ve found something new in the body and I’ve found different movements, different pathways, I’ve found different textures in my body and that’s really nice because it feels really authentic.

You’ve described Dharawungara as a ‘collision of rituals’. What is it about ritual that is inspiring you and which elements of this idea have you been exploring thus far?

This is a kind of new interest for me and it’s come out of a want to learn more about my ancestry and my family. I’ve been on a journey over the last few years. I’ve always identified as Wiradjuri, as Aboriginal, and over the last few years I have been asking what does that actually mean? What does that mean today in 2018? What does it mean to be an Indigenous choreographer and an Indigenous man? And that can mean lots of things, it could mean learning the language, being a political activist, being a community organiser, but because dance is my practice and dance encodes the law, and was past on from generations to generations through ritual I have kind of been looking closely at it and saying yes it is ritual that I am interested in. And the thing that I am increasingly wanting to explore more as a choreographer more than anything else is how I can use my art to bring back ancestral ritual and practice down here in the South East. I’m going to be doing this at Chunky Move which is super exciting!

Joel Bray’s new work Dharawungara is presented as part of Chunky Move’s Next Move commission NEXT MOVE 11, a dystopian double that also features new work ‘Nether’ by emerging Choreographer Lauren Langlois from 8 – 17 November. Book now here.

Photography: Pia Johnson.